About me

I am a physical oceanographer interested in ocean physics, climate, forecasting and modelling. My research focuses on how processes acting on small-scales, such as turbulent mixing and mesoscale eddies, influence the large-scale ocean circulation and its variability. I use theoretical techniques combined with a range of idealized and realistic ocean models and analysis of oceanographic data to better understand interactions across scales in the ocean in order to represent them properly in low-resolution models.

I obtained my PhD in 2016 from Stanford University. Between 2016 and 2021 I held several postdoctoral positions at the University of New South Wales in the Climate Change Research Center and the School of Mathematics and Statistics. In 2021 I joined the School of Geosciences at the University of Sydney as an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) Fellow. In 2023 I joined the Bureau of Meteorology as a Climate Scientist working in research.

Research Interests

My research interests include:

Equatorial dynamics, turbulent mixing, tropical instability waves and tropical climate variability and predictability: I am interested in equatorial dynamics and in particular how processes on short timescales (months to seconds), such as Tropical Instability Waves (TIWs), internal gravity waves and small-scale turbulence, influence the large-scale tropical circulation, tropical modes of variability such as the El-Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and their predictability. My PhD work focused on TIWs and their role in driving mixing in the equatorial Pacific (e.g. Holmes and Thomas 2015 J. Phys. Oceanogr.). I have shown that the chaotic nature of TIWs influences ENSO predictability (Holmes et al. 2019 Climate Dynamics). My ARC DECRA project Mixing and air-sea coupling in the Pacific: Toward better El Nino forecasts aimed to isolate the impact of air-sea interactions at the mesoscale on the tropical Pacific circulation in order to understand (and ultimately reduce) biases in global climate models used for climate projections and predictions (e.g. Holmes et al. 2024).

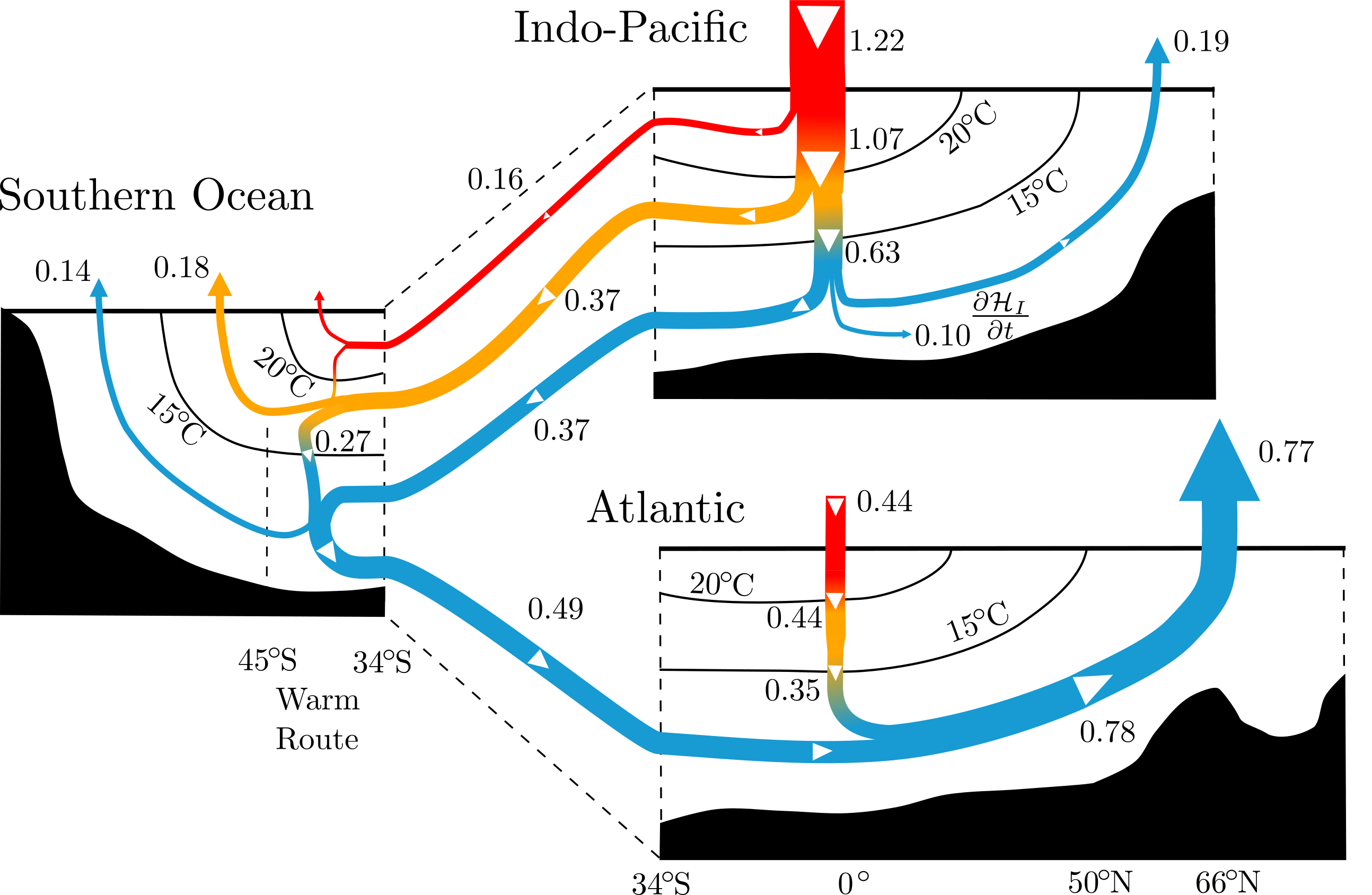

Ocean heat transport in thermodynamic coordinates: The ocean is warmed by air-sea heat fluxes at low-latitudes and warm temperatures and cooled in the mid- and high-latitudes at colder temperatures. To maintain a steady state the ocean must therefore move heat not only from low to high latitudes (meridional heat transport), but also from warm to cold temperatures (diathermal heat transport). By developing a suite of novel heat transport diagnostics within the MOM5-based Australian community global ocean model ACCESS-OM2, I have shown that the ocean’s diathermal and meridional heat transport depends on parameterized diffusive mixing processes (Holmes et al. 2018 J. Phys. Oceanogr., 2019 Geophysical Research Letters). This diagnostic framework allows the role of mixing processes to be isolated and quantified, including the `artificial’ numerical mixing arising from the numerical discretization of tracer transport Holmes et al. 2021 J. Adv. Mod. Earth Sys..

Global ocean modelling: I have contributed to the development of Australia’s global ocean modelling system, ACCESS-OM2, through the Consortium for Ocean and Sea Ice Modelling in Australia (COSIMA). I performed the 1/4-degree ACCESS-OM2 simulations that were contributed to the international Ocean Model Intercomparison Program (OMIP-2) portion of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Program Phase 6 (CMIP6). I have contributed to the development of the diagnostic packages within the MOM5 code base, contributed analysis examples to the COSIMA cookbook and mentored students and postdocts throughout the COSIMA community on the use (and abuse…) of ACCESS-OM2.

Subseasonal to seasonal coastal sea level prediction: My position as a climate research scientist at the Bureau of Meteorology is within the seasonal forecasting group and focused on the subseasonal-to-seasonal (several week out to one year lead time) prediction of coastal sea level variability. By combining tide predictions, sea level rise projections and storm surge statistics with subseasonal-to-seasonal sea level forecasts from the Bureau’s seasonal prediction model, ACCESS-S2, I am developing a forecast system for total water level around the coastline that can be used to provide outlooks for coastal flooding risk for upcoming seasons. This work, funded by the Australian Climate Service, is aimed at increasing resilience of coastal communities to sea level rise and assisting with climate adaptation.

Abyssal ocean circulation and mixing: I have contributed to our knowledge of how diapycnal mixing in the abyssal ocean and influences abyssal ocean circulation and the conversion of Antarctic Bottom Water into lighter water. As mixing in the abyssal ocean is seafloor-intensified the topography of the seafloor has a strong influence on abyssal circulation pathways (de Lavergne et al. 2017 Nature and Holmes et al. 2018 J. Phys. Oceanogr.). I have shown how these features of abyssal ocean circulation influence tracer transport in order to inform future field tracer release experiments (Holmes et al. 2019 J. Phys. Oceanogr.).

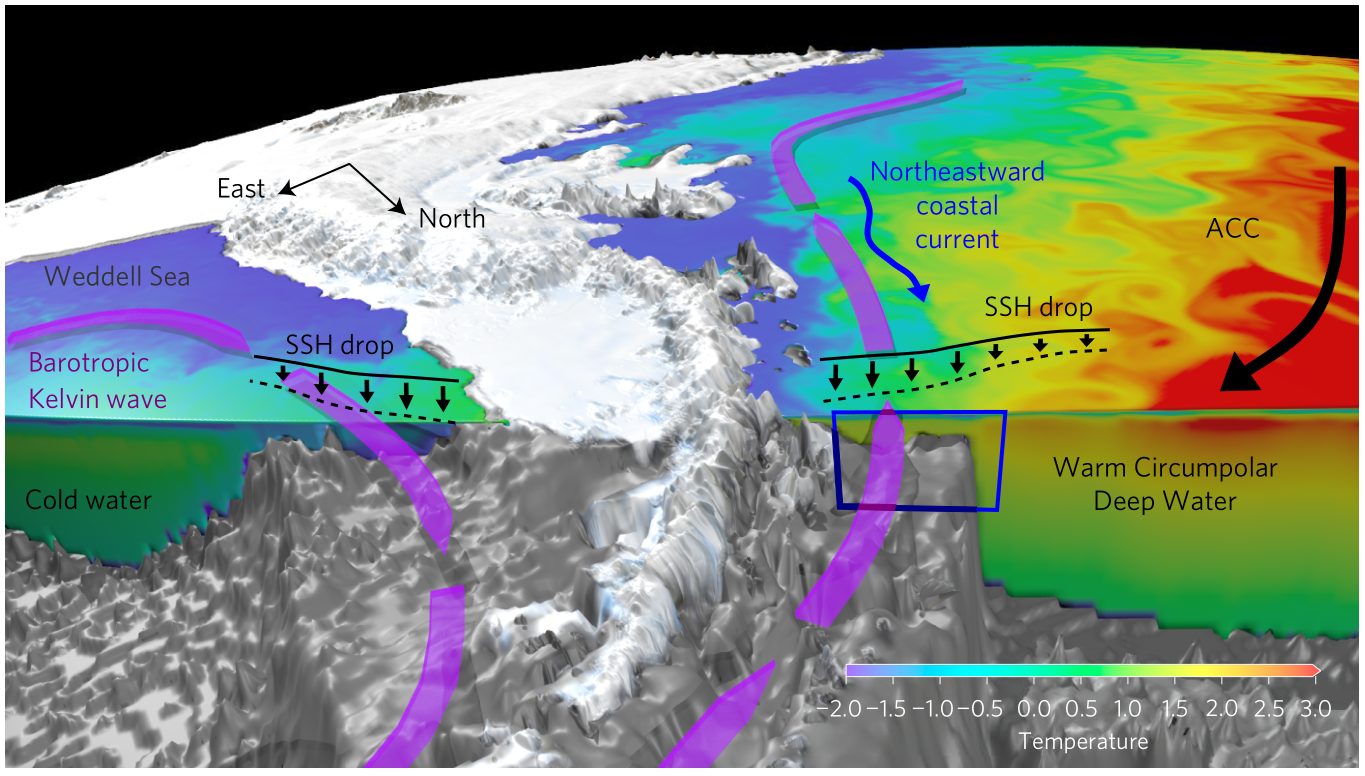

Antarctic coastal circulation and ice shelf melting: I have also contributed to a series of PhD student projects aimed at understanding the mechanisms that drive warm Circumpolar Deep Water onto the Antarctic continental shelf and into contact with vulnerable ice shelves, with worrying implications for global sea level rise. One such mechanism highlighted by our work involves the transport of heat onto the continental shelf by bottom Ekman transport associated with coastally trapped barotropic waves Spence, Holmes et al. 2017 Nature Climate Change.

This website contains my CV, a list of publications, conference talks and a short summary of some of the projects that I am currently involved in.

If you wish to know more or have any other questions, please contact me at ryan.holmes@bom.gov.au